Packing our heads full of dirt

Erik and I spent the better part of this week sitting on our butts – all in service of becoming smarter, more successful farmers. We were lucky enough snag two scholarships to the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture’s Young Farmers Conference in Pocantico Hills, NY – a three-day whirlwind of workshops ranging from BioChar to soil science to Field Songs to Slow Tools to cover crops. Our heads are full to the brim and I’m only now starting to sift through the information dump. Here are some of my takeaways:1. Farmers don’t have to be poor.This man: (Richard Wiswall) is a genius.

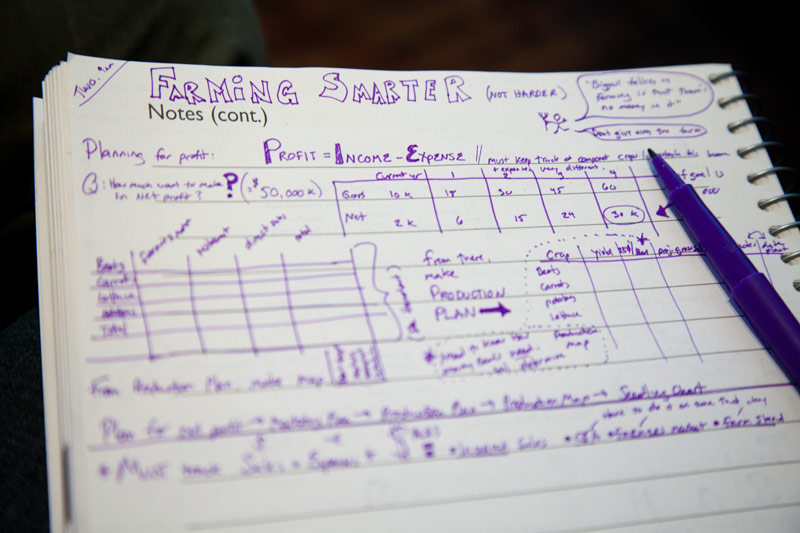

Erik and I spent the better part of this week sitting on our butts – all in service of becoming smarter, more successful farmers. We were lucky enough snag two scholarships to the Stone Barns Center for Food and Agriculture’s Young Farmers Conference in Pocantico Hills, NY – a three-day whirlwind of workshops ranging from BioChar to soil science to Field Songs to Slow Tools to cover crops. Our heads are full to the brim and I’m only now starting to sift through the information dump. Here are some of my takeaways:1. Farmers don’t have to be poor.This man: (Richard Wiswall) is a genius. Or, rather, he’s at least the savior of my sanity as we venture down this new and very uncertain path to Farmerdom. He taught a workshop called “Farming Smarter, Not Harder,” which helped to counter our (my) fear that we’ll be stepping off a financial cliff the second we cast our lot with carrots, cows and kale. Fear not, says Wiswall. “The biggest fallacy in farming is that there’s no money in it.”A tall, wiry man, Wistwall dressed to reflect his success as a businessman famer (smart black vest paired contrasted with practical jeans) and he kicked off his presentation with what he called “farm porn:” several dozen tantalizing photos of his well-capitalized Vermont farm in full productive swing, nary a skinny, forlorn wretch in sight. Making money farming is simple math, he said. “Profit equals income minus expenses.” It’s not complicated as long as you keep emotions out of decision-making. Keep meticulous records of what you spend on materials, equipment and time. Subtract that total from your gross income. If the remainder is negative, reevaluate your expenses or your sale price or both or abandon that specific enterprise in favor of something cash-flow positive. And above all, “Do not work for free,” he said, citing the countless farmers who work 80+ hours a week to get by and burn out. “We should be able to pay ourselves well, we should be able to pay our help well and everybody wins.”

Or, rather, he’s at least the savior of my sanity as we venture down this new and very uncertain path to Farmerdom. He taught a workshop called “Farming Smarter, Not Harder,” which helped to counter our (my) fear that we’ll be stepping off a financial cliff the second we cast our lot with carrots, cows and kale. Fear not, says Wiswall. “The biggest fallacy in farming is that there’s no money in it.”A tall, wiry man, Wistwall dressed to reflect his success as a businessman famer (smart black vest paired contrasted with practical jeans) and he kicked off his presentation with what he called “farm porn:” several dozen tantalizing photos of his well-capitalized Vermont farm in full productive swing, nary a skinny, forlorn wretch in sight. Making money farming is simple math, he said. “Profit equals income minus expenses.” It’s not complicated as long as you keep emotions out of decision-making. Keep meticulous records of what you spend on materials, equipment and time. Subtract that total from your gross income. If the remainder is negative, reevaluate your expenses or your sale price or both or abandon that specific enterprise in favor of something cash-flow positive. And above all, “Do not work for free,” he said, citing the countless farmers who work 80+ hours a week to get by and burn out. “We should be able to pay ourselves well, we should be able to pay our help well and everybody wins.” I’m simplifying his message here – he spent more than three hours taking us through detailed budgets for hypothetical crops and outlining how to frame up priorities in a farm operation. My notes look like I dropped acid with my breakfast eggs. But I left the room with the distinct feeling of possibility – specifically, that a solvent life farming is indeed possible – which put a spring in my step for the rest of the day.2. Dirt is mind-blowingly complex and almost irreplaceable.Yes, dirt – as in, “dirt cheap.” Well, it turns out you couldn’t buy the stuff if you tried. Here’s how to make dirt: start with rock (the ‘parent material’). Add wind and rain and sun and snow. Wait about a million years. Let microbes do their work feeding on the minerals until a mix of organic matter and rock particles form (the ‘subsoil’). Wait another eon or two while the topsoil forms. (Hark! We’ve just crossed into A.D.) Now agriculture can begin.But not for long. The crazy thing is, just plowing dirt degrades its structure, disrupts its biology and destroys precious organic matter – while making it vulnerable to erosion. And this is how our grandfathers’ generation had it all wrong: the settling of America was driven largely by farmers tilling fields to death and then abandoning their land in search of virgin ground – usually westward. (Enter the dust bowl.) Then technology developed during the World Wars that spun off nitrogenous fertilizers and suddenly farmers could do an end-run around soil chemistry – for a time. But buying more time comes at a high cost: ever-increasing inputs of fertilizers, pesticides, water and petroleum. And the sad truth seems to be that most farmers in human history haven’t figured out how to use dirt to make food without killing it in the process.

I’m simplifying his message here – he spent more than three hours taking us through detailed budgets for hypothetical crops and outlining how to frame up priorities in a farm operation. My notes look like I dropped acid with my breakfast eggs. But I left the room with the distinct feeling of possibility – specifically, that a solvent life farming is indeed possible – which put a spring in my step for the rest of the day.2. Dirt is mind-blowingly complex and almost irreplaceable.Yes, dirt – as in, “dirt cheap.” Well, it turns out you couldn’t buy the stuff if you tried. Here’s how to make dirt: start with rock (the ‘parent material’). Add wind and rain and sun and snow. Wait about a million years. Let microbes do their work feeding on the minerals until a mix of organic matter and rock particles form (the ‘subsoil’). Wait another eon or two while the topsoil forms. (Hark! We’ve just crossed into A.D.) Now agriculture can begin.But not for long. The crazy thing is, just plowing dirt degrades its structure, disrupts its biology and destroys precious organic matter – while making it vulnerable to erosion. And this is how our grandfathers’ generation had it all wrong: the settling of America was driven largely by farmers tilling fields to death and then abandoning their land in search of virgin ground – usually westward. (Enter the dust bowl.) Then technology developed during the World Wars that spun off nitrogenous fertilizers and suddenly farmers could do an end-run around soil chemistry – for a time. But buying more time comes at a high cost: ever-increasing inputs of fertilizers, pesticides, water and petroleum. And the sad truth seems to be that most farmers in human history haven’t figured out how to use dirt to make food without killing it in the process. The short story is this: plant nutrition depends on delicate soil chemistry as well as the microbial life within the soil. Plants need the Big Three – nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus – as well as a dizzying array of lesser trace elements. And if the chemistry’s off, it’s totally possible for a plant to be practically swimming in potassium but unable to use any of it. There’s something called a “cationic exchange capacity” that roughly correlates to how available nutrients are, and it’s influenced by everything under the sun. (We looked at a lot of charts, graphs and molecules during these workshops on dirt and if your head is spinning, I understand. Skip to point three.)

The short story is this: plant nutrition depends on delicate soil chemistry as well as the microbial life within the soil. Plants need the Big Three – nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus – as well as a dizzying array of lesser trace elements. And if the chemistry’s off, it’s totally possible for a plant to be practically swimming in potassium but unable to use any of it. There’s something called a “cationic exchange capacity” that roughly correlates to how available nutrients are, and it’s influenced by everything under the sun. (We looked at a lot of charts, graphs and molecules during these workshops on dirt and if your head is spinning, I understand. Skip to point three.) I truly don’t know how anyone keeps this stuff straight. But the takeaway is that if you take something out of the soil (by harvesting carrots, say), you have to put something back into the soil in the form of organic matter (such as compost). And once a field is done for the season, you have to protect it over the winter with a cover crop or much of the soil’s fertility and the soil itself will be washed away come springtime. Overall, it surprised me that modern organic farmers are still figuring out how to use soil sustainably and there are many conflicting schools of thought.3. The tools of economics have things to teach us – sort of.Stone Barns brought in an economist for the keynote address. Adam Davidson, of Planet Money/NPR/This American Life/New York Times renown, who gave 26-minutes of tough love to a room full of young, optimistic farmer-types on Thursday evening. He stopped speaking just in time to avoid the flying rotten tomatoes. I found his message both irritating and exhilarating.

I truly don’t know how anyone keeps this stuff straight. But the takeaway is that if you take something out of the soil (by harvesting carrots, say), you have to put something back into the soil in the form of organic matter (such as compost). And once a field is done for the season, you have to protect it over the winter with a cover crop or much of the soil’s fertility and the soil itself will be washed away come springtime. Overall, it surprised me that modern organic farmers are still figuring out how to use soil sustainably and there are many conflicting schools of thought.3. The tools of economics have things to teach us – sort of.Stone Barns brought in an economist for the keynote address. Adam Davidson, of Planet Money/NPR/This American Life/New York Times renown, who gave 26-minutes of tough love to a room full of young, optimistic farmer-types on Thursday evening. He stopped speaking just in time to avoid the flying rotten tomatoes. I found his message both irritating and exhilarating. “Your life is a luxury good.” This declaration instantly made Davidson lots of friends. He meant this: The overwhelming preponderance of humans who live and have ever lived have been motivated by the quest for adequate calories. Only in the last few centuries, and mostly in the last seventy years, have whole populations largely transformed into a leisure class held aloft by unparalleled material wealth and industrial production. This middle class was the perfect incubator for radical and evaluative thought which brought us the 1960’s-era, which sought to reject wholesale the world of our fathers.It is this capacity for radicalism, for liberal reflection, that Davidson is calling a luxury good. And I totally agree with him on this point. Most of the young farmers in the room are college-educated offspring from middle class nests, ourselves included. And now we’re looking to step sideways out of the middle class into an agrarian class while hoping to escape the same subsistence living that trapped generation upon generation of farmers before us.

“Your life is a luxury good.” This declaration instantly made Davidson lots of friends. He meant this: The overwhelming preponderance of humans who live and have ever lived have been motivated by the quest for adequate calories. Only in the last few centuries, and mostly in the last seventy years, have whole populations largely transformed into a leisure class held aloft by unparalleled material wealth and industrial production. This middle class was the perfect incubator for radical and evaluative thought which brought us the 1960’s-era, which sought to reject wholesale the world of our fathers.It is this capacity for radicalism, for liberal reflection, that Davidson is calling a luxury good. And I totally agree with him on this point. Most of the young farmers in the room are college-educated offspring from middle class nests, ourselves included. And now we’re looking to step sideways out of the middle class into an agrarian class while hoping to escape the same subsistence living that trapped generation upon generation of farmers before us. “Big agriculture views small farmers as market research,”This is a quote that Davidson read from a big-ag industry conference transcript which had us rolling in our seats with laughter: “It turns out that what consumers want in produce is flavor.” (Amazing insight, that.) He continued to paraphrase the results of this focus group: What people say they want when they say ‘local’ means all sort of things. The challenge for big-ag is to compete along these lines and deliver the intangibles that consumers seek with ‘local.’ In other words, the agricultural industry is analyzing the appeal of small farmers selling produce locally and trying to beat us at our own game. The problem is, they have billions of dollars and a hugely nimble industry in their corner. We have a few acres, compost and CSA’s. Which brings us to point three . . .“As our economy slows down, there will be less demand for premium produce at premium prices. The vision of a world sustained by local, organic produce is a fantasy.”Ooh, boy.Then he said twelve optimistic words, answered a few hostile questions and rushed away from the podium. After we had time to formulate a response, Erik and I caught up with him later to as him a few of our own questions, and to give him some soap.Davidson presented the perspective lent by the conventional lens of economics, which looks at the local food movement as an irrelevant outlier in a system governed by growth, consumption and inputs. But our response to Davidson is this: the premise of conventional economics is fatally flawed because it rests on the table of our natural world. As this grounding crumbles, so too do the economies reliant on it. Just look at the supply chain disruption that recent natural and climate events have wrought: hurricane Sandy knocking out power in the northeast, the 2010 eruptions of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano that grounded air travel over Europe, the roving drought zone in America’s breadbasket. These ‘externalities’ will become structural realities that will shred conventional market forces from the inside. To all of this, Davidson agrees. But he is providing a “what is” picture of current forces and has no faith that economies of scale will move in time to prevent the inevitable disaster. And to that, I unfortunately agree.

“Big agriculture views small farmers as market research,”This is a quote that Davidson read from a big-ag industry conference transcript which had us rolling in our seats with laughter: “It turns out that what consumers want in produce is flavor.” (Amazing insight, that.) He continued to paraphrase the results of this focus group: What people say they want when they say ‘local’ means all sort of things. The challenge for big-ag is to compete along these lines and deliver the intangibles that consumers seek with ‘local.’ In other words, the agricultural industry is analyzing the appeal of small farmers selling produce locally and trying to beat us at our own game. The problem is, they have billions of dollars and a hugely nimble industry in their corner. We have a few acres, compost and CSA’s. Which brings us to point three . . .“As our economy slows down, there will be less demand for premium produce at premium prices. The vision of a world sustained by local, organic produce is a fantasy.”Ooh, boy.Then he said twelve optimistic words, answered a few hostile questions and rushed away from the podium. After we had time to formulate a response, Erik and I caught up with him later to as him a few of our own questions, and to give him some soap.Davidson presented the perspective lent by the conventional lens of economics, which looks at the local food movement as an irrelevant outlier in a system governed by growth, consumption and inputs. But our response to Davidson is this: the premise of conventional economics is fatally flawed because it rests on the table of our natural world. As this grounding crumbles, so too do the economies reliant on it. Just look at the supply chain disruption that recent natural and climate events have wrought: hurricane Sandy knocking out power in the northeast, the 2010 eruptions of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano that grounded air travel over Europe, the roving drought zone in America’s breadbasket. These ‘externalities’ will become structural realities that will shred conventional market forces from the inside. To all of this, Davidson agrees. But he is providing a “what is” picture of current forces and has no faith that economies of scale will move in time to prevent the inevitable disaster. And to that, I unfortunately agree. So what to do?Well, Erik and I feel pretty clear-eyed about the up-hill financial march we may face as our economy and climate degrade. But we’re not moving our lives around to maximize our earning potential – we’re doing this to escape an economy that we viscerally don’t believe in and instead, aim to build from the ground up lives that reflect our values. We spend hours at the kitchen table parsing apart how to do this while remaining solvent, saving for retirement and supporting our soon-to-grow family. And we know that we will be stepping aside to a degree from the comfortable liberal cradle that birthed us. But the economy that I engage in every day of my conventional life is insanity, ecologically speaking, and this makes me despair. I just keep asking myself, ‘what else is this life for?’ On this, Erik, myself and probably even Adam Davidson agree: it’s not for the economy.

So what to do?Well, Erik and I feel pretty clear-eyed about the up-hill financial march we may face as our economy and climate degrade. But we’re not moving our lives around to maximize our earning potential – we’re doing this to escape an economy that we viscerally don’t believe in and instead, aim to build from the ground up lives that reflect our values. We spend hours at the kitchen table parsing apart how to do this while remaining solvent, saving for retirement and supporting our soon-to-grow family. And we know that we will be stepping aside to a degree from the comfortable liberal cradle that birthed us. But the economy that I engage in every day of my conventional life is insanity, ecologically speaking, and this makes me despair. I just keep asking myself, ‘what else is this life for?’ On this, Erik, myself and probably even Adam Davidson agree: it’s not for the economy.

* * * *

So after all that learnin’ and philosophizing, Erik and I scurried back to bucolic Athol to celebrate a December Saturday by splitting wood. (World’s-Best-T-Shirt courtesy of Erik’s classmate, Andrew.) Since we were away from the farm for most of the week, the week in pictures will return again next Sunday!

Since we were away from the farm for most of the week, the week in pictures will return again next Sunday!